boswellia carteri

“Pleasant, bubbly, woody, and inspiring. This fragrance is as lively as the trees from which it originates.”

Basic facts

● Species: Boswellia sacra syn. Boswellia carteri.

● Common name: Frankincense, Olibanum, Frankincense carteri.

● Chemical composition: a-pinene, limonene, myrcene,

sabinene, viridiflorol, d-3-carene,

incensole, boswellic acids.

Boswellia Certeri

ABOUTH THREE BOILOGY

Boswellia carteri trees are very physically variable, but are generally between 1.5 to 8 meters tall, growing directly on rocks or in sandy, rocky soil. It may be branched from the base or have a single trunk; the bark is brown or pale and papery. The trees have compound, imparipinnate leaves and white, five-petaled flowers that grow in dense bunches. The fruits are hard, not fleshy, and the seeds are wind dispersed. The trees can grow from sea level up to about 1400m in elevation and prefer areas where they can get access to frequent mists.

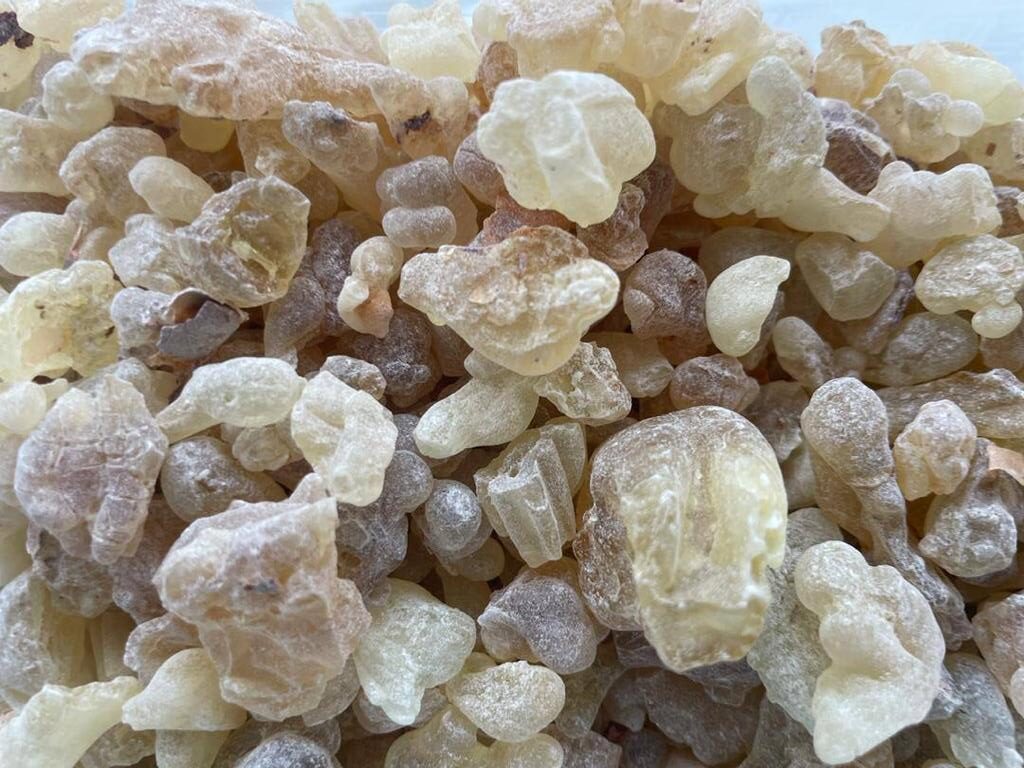

In Puntland, the trees are called by the Somali name, “Moxor.” Several types of the Moxor tree are recognized, depending on what the trees are physically like, what the resin is like, and where it’s growing: Moxor madow, Moxor lab, Moxor cad, Moxor dadbeed, and so on. The resin is called “Beeyo” and is incredibly variable; although it’s most commonly golden, yellow, orange, or white, some B. carteri resins are even black, red, green, or blue. This creates a dazzling rainbow of resins when they’re kept together.

A lot of botanists consider B. sacra from Oman and Yemen and B. carteri to be the same species. This is probably true botanically, but B. carteri is unique from B. sacra not only in some of its morphology, but especially in its fascinating chemical variation. Boswellia carteri is often thought to have one chemical profile and thus a particular smell, but this is because the resins are historically mixed and homogenized. When you experience resins from their individual farms, you realize that there is a delightful variety of scents and chemical profiles, from dark and smoky, to musky, to herbaceous and citrusy, to sweet, light, and floral. These single-origin resins are the trees’ true essence, and you can feel the differences depending on what the trees are experiencing.

Harvesting Systems

The trees are harvested by making small cuts into the bark and waiting for the resin to seep out. Typically, harvesters wait 14-18 days for the resin to harden before collecting it and re-opening the wound to allow more to come out. The harvest season often involves 8-10 of these tapping cycles and takes place between April to October. The trees are supposed to receive up to 12-16 cuts, depending on their size.

Most trees are clearly owned by an individual or family. Specific areas with trees, called “farms” by the harvesters, are owned by individuals, and passed down from father to son. The boundaries of each farm aren’t marked or written down but are well-known to each harvester–we are doing some of the first mapping to delineate and monitor each farm we source from.

Of course, sometimes harvesters feel pressure to put too many cuts on a tree, or to harvest a second time during the winter. This isn’t due to ignorance or irresponsibility on their part, generally, but simply by wanting to provide adequately for their families and improve their lives. This is why we’re conscious of the need to continuously monitor the trees from which we get our resin, work with the harvesters to ensure that they are being paid fairly and can provide for their families and help support the harvesting communities to develop sustainably.